A couple of months ago, I sent out an email asking what people’s biggest problems were or are with studying Chinese. I was overwhelmed by the responses I received from users of all levels and I have managed to whittle down everyone’s replies down to these 10 questions. Some of these learning problems came up again and again, and some even surprised me.

I want to thank everyone who replied to my email, and hopefully, the answers help other learners who are asking these questions now!

1. Chinese characters give me the fear! Where do I even start?

When I first started going to formal classes to learn Chinese, I said point blank that I was never going to learn Chinese characters. To me, learning to read Chinese appeared a near impossible feat, and so for years, and years I refused to even give a minute of my time to Chinese characters.

I remember being at a training course once where the trainer tried to explain how you might tell if a character was an ‘animal’ word. One of the people amongst our group, whose wife was Chinese, seemed to understand, but I sat with a blank expression, feeling like the BIGGEST. MORON. EVER.

So, as you can probably imagine, that didn’t do much for my confidence. It wasn’t until a few years later that my Chinese teacher who I’d been with for ages pointed out that we were reaching the end of the series of textbooks she used to teach with, and that it was time to move on.

To characters.

Fear gripped me. I felt sick.

My friend and I looked at each other with looks of dismay and unease, and finally after a lot of complaining and muttering and a considerable amount of convincing, we agreed. The next week, our teacher gave us each a pencil and the writing books with the ‘fields’, to teach us how to write some ‘basic’ characters.

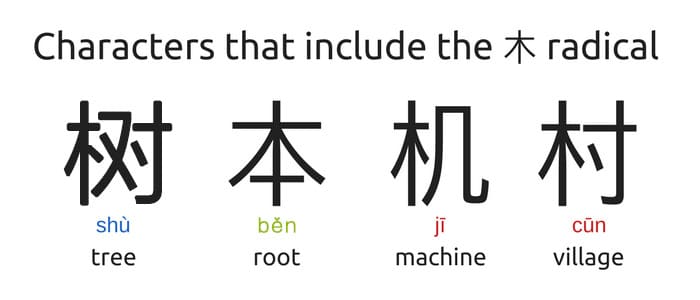

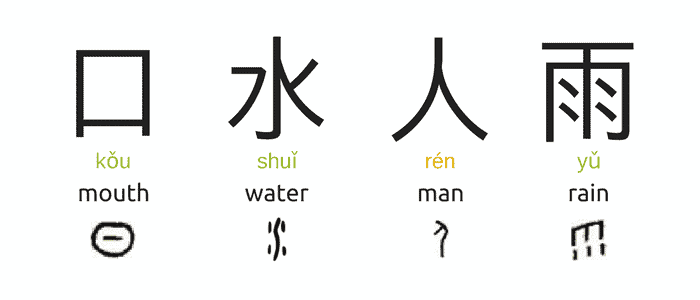

She started with what are called ‘pictograph’ or pictogram characters. These are characters that actually resemble the word that they represent, as a picture would

For starters, she taught us 木 (mù), which is the character for ‘wood’. I don’t think I need to convince you that it’s a pretty good likeness of a tree. Then, she told us that characters that include ‘木’, probably have something to do with wood. This was an absolute revelation. The fact that characters actually had meaning was a pretty big facepalm moment for me. I felt as though a veil had been lifted and I could see everything more clearly.

After that class, my interest in Chinese was completely renewed, and I was excited to have the next class and even did some practising at home. Obviously, at that time, they were shoddy attempts, but attempts there were!

I’m so glad that I eventually started to learn characters, because it really made me feel like I could express myself much more than before, and I kind of felt smart too. If only I’d had more confidence in myself to start learning sooner.

So, for all of you out there, who have the same fears as me, that Chinese characters are too difficult, that you don’t ‘get it’ at all and that learning to speak is enough, just try this:

- – Grab a pencil and paper

- – Open the Online Dictionary, and go to the details page for 口 (kǒu). (You can search ‘kou’ in English or with a Chinese keyboard to find the character)

- – Follow the stroke order in the GIF and try it for yourself.

Of course, not all Chinese characters are as simple as 木 or 口, they do get more complex, and FYI, even MORE interesting! BUT, if you want to just stick your toe in the water, I suggest beginning with some of these pictographic characters.

You learn more about radicals and their importance in our article, The Radical Truth.

Also bare in mind, that it’s WAY more fun if you learn to write the characters, especially if you can get your hands on a magic water pad, or field paper. For a lot of people, writing also cements the meaning of a character more fully in their memory.

Finally, what I have noticed more than anything, is that once I began learning to read and write Chinese characters my spoken Chinese REALLY improved. I was still a wuss about speaking in general, but I was making connections between words I knew how to speak with the corresponding Characters. I felt like I was on fire with new vigour for this language.

Don’t think that learning to read and write Chinese characters is a pointless endeavour or whatever, until you’ve given it a go.

2. I’m having problems remembering characters! Can you recommend some ways to help me remember?

One of the ways in which most people try and remember characters is by staring hard at them, hoping they will somehow leave a permanent imprint on their brain. I’ve been there. I made my own (terribly written) flashcards, that were sometimes so bad, I couldn’t even recognize my own characters! Not only is this method slightly soul destroying, but it takes a lot of time.

One of most thorough ways to learn a Character is to look at the radicals that make up the character. Radicals, are the building blocks that make-up a character and often allow us to understand the meaning behind a character and remember it more easily.

Far too often, Chinese learners forget how to write Chinese characters that they have already studied many times before. Even native speakers get frustrated with forgetting how to write characters! If this has been happening to you, it’s time to stop beating yourself up about it. Instead, let’s pause for a moment and consider a new strategy for retaining Chinese characters in the long term.

To recall characters with ease, you must learn to use your brain as it was intended to be used. Your brain is not wired to memorize large volumes of meaningless shapes in the form of Chinese characters. To really make your character-learning stick in your brain (as well as make it more enjoyable) you must make your Chinese learning associative. To do this, create a sentence or “story” that depicts each character’s meaning. If the story is funny or interesting to you, it will not be burden to remember it.

When you create associative memory hints for learning Chinese characters, use the radicals in the character to construct a sentence that helps you associate the character with its meaning. You can even add a hint to the pronunciation of the character in the story, or multiple meanings for characters that have broader meanings. The point is, the story must be meaningful to you. In this way, it becomes hard to forget.

糕 (gāo) means “cake” and the radicals that make up this character mean “rice”, “sheep” and “fire”. To remember all of this information, you can put it into a sentence like the one appearing in the image above. Creating a silly image to go along with the character is also useful in remembering the story.

Look through the next few examples to get an idea for how you can create your own stories. If you haven’t learned any radicals before, check out the article The Radical Truth.

This one is nice and simple. We see a man radical and a tree radical combined to create the character which means “to rest”.

Here’s another nice and simple one, where it doesn’t take too much brainpower to come up with a story. You might also remember this character by thinking that a son and a sheep both need to be raised by someone.

In the example above, the pronunciation of the character is also hinted at within the story. The name “Gene” kind of sounds like “jin”, the character’s pronunciation. Decide whether this is useful to you and add hints to some of your stories to help you remember the pronunciation.

In the beginning, creating the stories to help you remember characters is a bit challenging. After you have done a few it gets much easier and eventually becomes second nature. Some characters don’t work quite as well as the ones mentioned above, so you need to get a bit more creative. Read all about how to create stories for any character here.

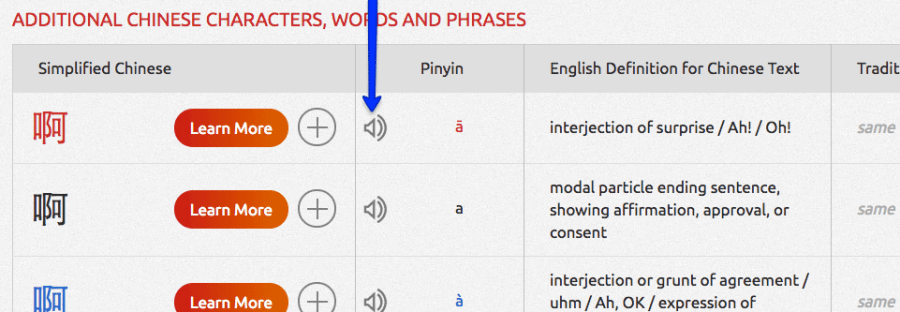

Add your stories and pictures to the comments section of the Learn More pages of the Written Chinese online dictionary. This way you can refer back to them easily should you need a reminder of what you created. You can also look in the comments section to see the stories that other learners have created. Click the Learn More button next to any dictionary entry and scroll down to find the comments section. We use Disqus for our comments, so you can even follow other learners and get notified when they add something to these pages.

It took me quite some time to realise how important context can be within Mandarin Chinese, in both the written and spoken language.

Since we’re primarily discussing characters here, I found that learning bigrams (2-character combinations) instead of characters was easier because you have the context of another character to help you remember. For example, I would also confuse 米 meaning ‘rice’ and 来 meaning ‘here’. Not only was it unlikely for ‘rice’ to pop up in a sentence when food hasn’t been mentioned, but I would often look for the characters before and after to figure out whether it was 米 or 来. Obviously, this doesn’t work for all characters, but it does help in the initial stages of studying. You can take a closer look at to remember these ‘similar’ looking characters in our article, How to Learn Chinese Characters That Lookalike.

Remembering Characters for Exams

This is a small addendum, but something I wanted to address about remembering characters for an HSK exam (someone mentioned they struggled with this). If you’re not sure what an HSK exam is, take a look at our article, Want to know how to take an HSK test? Here are 9 Tips!

As with all aspects of the HSK exam, the best way to remember the characters is to take practice tests beforehand. There is plenty of material out there, including on the official HSK website to help you prepare for the exam. Not only that, but the vocabulary you need to study is available for free, including on our site as downloadable PDFs.

Finally, there are HSK books available with several tests inside that also include CDs for the listening tests, and answers in the back of the book for you to check them later. We have several listed in our Chinese Book Shop that you can take a look at.

If you’re really struggling to prepare for the exam, you might also consider taking a class or two with a tutor, either in a classroom, or online by using a platform such as italki.

3. How do I remember the Pinyin?

Although Pinyin is the romanisation of Chinese characters, you still need to learn Pinyin, because many of the pronunciations do not follow the same rules as English. This can be a challenge for new students of Chinese, but learning the rules of Pinyin from the beginning will improve your pronunciation in the long run.

I’ve joked before about my first experiences of the Chinese language, and only really remembering words that I could connect to English. For example, I picked up 没有 (méi yǒu) pretty quickly, because I associated it with ‘mayo’, like mayonnaise. I also learned certain words faster because I either needed to use them a lot 要 (yào) / 不要 (bù yào) or because I heard them all the time 喝水 (hē shuǐ) / 快点 (kuài diǎn). However, for many learners, this kind of learning is impossible, because they’re not living in China, or close to a large Chinese population.

I have never come across a walkthrough for learning Pinyin, you just have to learn in, and learn it good, otherwise, your pronunciation will be rubbish.

So let’s start with the basics:

There are only so many pinyin to learn, similarly to the alphabet, and the best way to get these down, is by using a Pinyin chart and practising the pronunciation by listening to audio and speaking out loud. Ideally, having a native speaker correct your pronunciation is a good idea as they can also show you how to shape your mouth to make the correct sound.

As you can see from the chart, there are letters along the X and Y axis, and the words inside are combinations of those.

So, once you have learned that the rule for ‘b’ is that it is pronounced ‘buh’ like as in ‘ball’ and ‘a’ is ‘ah’ as in ‘apple’, combined together you can produce ‘bah’ for pronunciation of ‘ba’.

Listen to the pronunciation:

If you follow this link to our dictionary, I have added all the Pinyin in the first column, so that you can tap on the ‘audio’ button (red or black characters are best) and listen to the sound. Forget the tones for now, just get the sounds right.

When you get stuck with the pinyin, you can type it into the Online Dictionary, and listen to the pronunciation.

Some other methods to help you learn Pinyin is by watching Chinese TV that has Pinyin for you to follow. You can check out the Learn Chinese with Movies YouTube channel for videos like this.

I’m saving the best till last, and suggesting that you watch a video that was made to teach Chinese kids Pinyin. They’re ridiculously annoying, but catchy and helpful.

This one also has a fun bit for tones at the end 😀

4. I’m never going to be able to speak Chinese like a native! How can I improve my pronunciation

I know, Chinese pronunciation and tones can be a challenge! I was always so embarrassed about speaking that I allowed other people to take charge or the conversation and deal with things for me. This was such a mistake, and I wholeheartedly regret not just getting over myself and speaking the best I could. So what if the occasional person makes a comment?

From my experience, the majority of people would be impressed by the smallest amount of Chinese I was able to speak. Your pronunciation and tones will NEVER improve unless you suck it up and speak. In our free 30 Days Learning Guide, Nora recommends recording yourself speak with your phone and play it back to yourself. I know, hearing yourself is awful, but it’s really worth giving it a go!

Next, try watching TV shows, listening to radio or podcasts and even conversations between Chinese people. It’s really easy to switch off when you’re listening to a language you don’t understand, but try and just pick out a few words. You might even add them to your study list in the dictionary, or write them in a notebook to learn them later!

On the topic on TV, take a look at this video that shows you how your mouth should look when pronouncing Chinese:

Tones are another area of spoken Chinese that many non-natives struggle with, just because it’s so foreign. Probably the more musical students, find tones easier to get to grips with, but it is possible for everyone to speak Chinese with tones.

You can test your tone knowledge by using our Chinese Tone Trainer. Listen to the sound, and select the correct tone.

There are more tips for remembering Chinese tones, in this article about improving tones.

5. If one sound can have so many meanings, how will I ever understand when someone talks to me?

You’ve probably heard it often, but over time you will begin to hear the difference between tones.

However, it is also true that some characters have multiple meanings, known as 多音字 (duō yīn zì).

Context

One of the ways to tell the meaning of a word spoken in Chinese is basically down to context. This means that as well as listening to the words spoken, you are also considering the situation that they are spoken in.

I often use the example of ‘ma’ characters. The common words that have the ‘ma’ sound are 妈 (mā) ‘mother’, 马 (mǎ) ‘horse’, 嘛 (má) meaning ‘numb’ and 吗 (ma) a question particle. Each of these examples have quite different meanings, and therefore, even if your tones aren’t so hot, you can gather from their usage in a sentence whether someone is referring to their mother, a horse, whether something is spicy, or asking a question. Furthermore, since few characters are spoken as single characters, but rather found as a bigram (2 character combination), it reduces the chances of confusion.

In my mind, I don’t hear one character’s sound and consider it’s meaning, I often rely on it’s meaning in relation to the other character it’s combined with. Even now, it’s the single characters that trip me up in a conversation, and I get so wrapped in trying to work out the meaning, I miss half the conversation.

Of course, there are examples of bigrams that sound the same, and even have the same tone, but with context you can surmise which words they are speaking. For example, the characters for ‘angry’ and ‘voice’ are different, but have the same sound.

生气 shēng qì

声气 shēng qì

It’s unlikely that a person would be saying ‘我声气了‘ - ‘I’m a voice’, whereas they are more likely to be saying ’我生气了‘ ‘I’m angry’.

Tones

The other big issue here for most people are tones. The five tones help distinguish between different words, for example let’s look at the ‘ma’ example again. Not only are we helped to distinguish between them by context, the bigrams they appear in, but also by the tone.

Ignoring tones, will ultimately make learning Chinese more difficult and will cause more harm than good long term. Not only do you need them to understand what people are saying to you, but also for them to understand you!

Speaking Quickly

It is also true, that a lot of native Chinese people speak very quickly and with an accent. Knowing about the the Hunan Province ‘f’ instead of ‘h’ would have really saved me a lot of pain and misery when I first came to China! When you first begin to learn Chinese, just learn some simple phrases to ask a person to speak slower, or repeat a sentence. Although I needed to do this throughout my time in China, I find the majority of people understand that they might need to repeat a certain phrase, speak slowly and even help you learn more about the Chinese language. Shopkeepers and taxi drivers are particularly good people to talk to, especially when you’re learning basic phrases. You can also ask someone how to say something in Chinese and many people are keen to teach!

Useful Phrases When You Don’t Understand

I don’t understand. (wǒ bú tài míng bai) 我不太明白。

What do you mean? (shén me yì si) 什么意思?

Please repeat that. (qǐng zài shuō yī biàn) 请再说一遍。

How do you say that in Chinese? (zhè ge yòng hàn yǔ zěn me shuō?) 这个用汉语怎么说?

6. How Can I learn Chinese quickly?

“學而時習之,不亦說乎?有朋自遠方來,不亦樂乎?人不知而不慍,不亦君子乎?”

Confucius – Analects

This quote from Confucius describes the importance of commitment and perseverance in learning and gaining respect from other people, even if you don’t get any notoriety for it.

My feelings on learning Chinese quickly is that if you think you have, you’ve probably cut corners and have only ‘learnt’ the bare minimum.

Unless you completely immerse yourself into the Chinese language, refuse to speak your native tongue and just go all in, there’s no ‘quick’ way to learn Chinese.

There are ways to make the learning process smoother, simpler and maybe easier, but in general, like learning any language, they require patience and commitment.

Here are some things you can try:

- – Get a Chinese tutor who doesn’t speak your native language well, and go from there. You have no choice but to speak Chinese.

- – Do a language swap with a Chinese native who wants to improve their English or other language. Meet for a coffee and spend half the time on Chinese, and the other in English.

- – Start from the beginning. Learn the proper pronunciation, learn tones, maybe study something on Chinese culture (this can be quite helpful when you move on to Chinese characters), learn Chinese radicals. If you skip an area, you’re destined to struggle with Chinese, unless you backtrack (definitely not the quick way’ and have to learn from scratch.

- – Take an intensive course

- – Do everything in Chinese: change your mobile’s language, only watch Chinese TV shows, listen to Chinese music and speak Chinese!

7. I noticed there are colours on the words in the dictionary. What do these mean?

Yay! I get a chance to talk about the dictionary! If you’ve used the Online Dictionary, the characters and pinyin are either red, yellow, green, blue or black.

These colours are used to denote the ‘tone’ of a character. Mandarin Chinese is a tonal language, that has 5 tones (4 actual tones and a neutral tone). Since there are only a certain amount of ‘words’ in Chinese, the tones help expand the amount of words by creating a different pronunciation.

The tone colours are basically meant to help visual learners. You see a red character, you know it should have a flat tone. Yellow, a rising tone; green a falling and rising tone and blue a falling tone. Black is a little more complicated and can depend on the previous character tone.

If the colours distract you, it’s’ OK I get it. You can turn these off, so that all the characters are just black.

8. TENSES?!

The truth is, the Chinese language technically doesn’t have tenses, and you’ll hear lots of people say this is why Chinese is ‘so easy’. It’s only easy if you know it, so getting your head wrapped around ‘tenses’ or the lack of them can be challenging.

When I asked people to help me with this article, a lot of people wrote ‘tenses’ as being a problem, and our article on ‘Tenses’ is one of the most visited posts on our blog…

What does that tell you?

If you’re struggling to understand how to talk about the past, present and future in Chinese, take a look at our article, Past, Present and Future Tenses in Mandarin Chinese for more info!

9. What’s the difference between a single character and 2 characters together?

Whilst a single character can have multiple meanings, a bigram (2-character combination) usually narrows down the meaning.

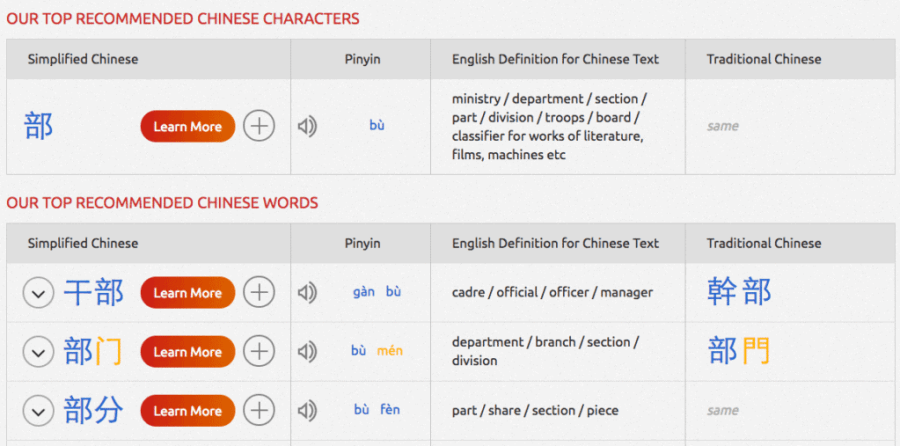

For example, 部 (bù) has the following definition: ministry / department / section / part / division / troops / board / classifier for works of literature, films, machines etc

How do you know which one to use?

Well, that’s where bigrams come into play.

When 部 (bù) is combined with another character, for example 门 (mén), the meaning is narrowed down to ‘department / branch / section / division’. Since these words are synonyms in English, they can be used interchangeably.

As you can see from the definition of 部, the word ‘department’ is included, but it’s only when it’s used with 门 that the meaning is more specific.

Similarly, when 部 is combined with 分 (fèn) meaning ‘part / share / ingredient / component’ the translation is more specifically ‘part / share / section / piece’.

You can learn more about bigrams and their usefulness in our article, The Chinese Bigram: Why Learning Chinese Characters is Easier in Twos.

10. Am I meant to use punctuation in written Chinese?

The short answer is yes, you do use punctuation in written Chinese.

Although there are particles in Chinese, such as 吗 (ma) which produces a question, a question mark, also known as 问号 (wèn hào) should be used in written Chinese.

Similarly, full stops, commas and exclamation points are used in the way as in English.

There are some additional punctuation marks, such as the back comma, and the middle dot, which is used to mark a western name. The guillemet are used to mark a book, film title etc.

You can learn more about Chinese punctuation in our article How To Use Chinese Punctuation And Keyboard Input.

Please feel free to share you thoughts, opinions and experiences of learning Chinese! Did you have any of these questions? How did you figure it out?

If there are areas we didn’t cover in this article that you feel need to be answered, leave your comments below!